Live Kindly, Tread Lightly -Animals and Us

Occasional book reviews and recommendations, but the focus here is mainly on animal advocacy: news of campaigns, and interviews with inspirational people who try to make the world a kinder place.

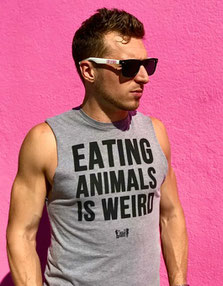

Animal Advocate no.10: Mark Wakeling of Amberwood Animals

Mark Wakeling runs his animal sanctuary, Amberwood Animals, near Bicester in Oxfordshire. This follows a career first in the army and then as an actor, later running his own acting school until Covid hit in 2020.

Linda: How did the sanctuary start? Did you decide to start one and go looking for suitable land?

Mark: No, I had no idea that this was going to happen. I ran my acting school and was living in my own cottage near here, but because of Covid I lost the business after desperately trying to make it work. I had no choice but to liquidate the company and was plunged into quite a lot of debt.

Before Covid I’d been running song circles locally – mantra singing, medicine songs. Through that I met a local farmer’s daughter, Jo, who’d recently lost her husband, quite young. She was from a beef farming family so I was intrigued that she was interested in the song circle, not being the typical sort of person who came along. We became friends, and I visited the farm; then Covid came, and after lockdown I learned that her father had died and the farm’s future was uncertain. I offered to come and help out. There were animals here – 10 beef cattle and 20 sheep; I learned how to look after them and did various jobs such as building fences and tractor work.

Jo wasn’t ready to invest in anything new, but before long I had the idea of raising enough money to buy those animals from her, to form a sanctuary here, and to pay her rent for the land. I borrowed £10,000 from a mate to buy the animals, and that’s how it all started.

Once I owned them I took on more responsibility. There are all sorts of legal requirements to owning animals. As far as the outside world is concerned I’m a farmer, in that I’ve gone through all the necessary legal procedures.

Linda: Have you acquired other animals since?

Mark: Yes, next came the pigs. I’ve got five – the first was Olive, who’d been a pet pig. Then there are ten or so sheep that I’ve bought in from various places. I’ve learned that there’s a whole spectrum of animal farmers, ranging from hardcore factory farmers who see animals as just objects on a conveyer belt, to those on smaller farms who sometimes have an animal that’s special to them. One of the lambs came from a farmer who had a soft spot for this particular orphan and asked me to take him. This week I’ve added two lambs from a small rare breed farm – they were orphaned and undersized, so the owner wanted to find a place for them. I don’t go looking for animals but if I hear about one that needs a home, I’ll follow it up.

L: How do you finance the sanctuary? There must be considerable costs for food, veterinary treatment, equipment and maintenance. Do you have regular donors? Is your sanctuary eligible for any government grants?

M: A mixture. I funded it to start with by selling my cottage and I’ve still got some of that left. The costs are about £40,000 a year, without paying anyone or any of the extra costs – this is just feed, rent, utilities, vet bills, the contractors I have to get in sometimes. It works out at about £900 a year per animal – and there’s insurance now that we’re a charity, too. Just about half comes in from donations and one person donates most of that – thank God for her. I’ve had a few grants, from GenV and other sources.

L: What’s your typical day on the sanctuary?

M: I start very early – it’s all about routine, and I stick to rigid timings. 7am is feed time for the pigs, then I feed the elderly sheep who live in the barn (they’re arthritic, and not out on the grass); after that, it’s picking up poo, an important daily task, and giving pain-killing injections to some of the older sheep. At 10.30 the pigs get carrots and apples. Then it’ll be whatever needs to be done. I function best in the morning. At the moment I’m building a sheep shelter, more or less single-handed – an enormous structure. I need to spend time catching up on emails and admin, checking all the other animals out in the fields, going out to buy carrots etc as well as providing for myself.

But of course it depends very much on what time of year it is. So it varies, but it comes down to that routine. Afternoon feed for the pigs is about 4pm. I like to feed them carrots and apples at that time, to keep them interested in these key moments of the day. When you see how pigs behave, you realise that they like space, they’re often quite widely spaced out. Seeing that, I realise how terrible it is to keep pigs crammed together in intensive farms, how it denies them that natural behaviour.

L: You’ve recently had the heartbreak of losing Bambi, one of your quite young cows, to TB when she tested positive. That obviously hit you very hard. If she’d had to be taken away to a slaughterhouse you’d have seen that as a terrible betrayal (luckily she didn’t …) Losing animals, taking the decision to end their lives if they’re suffering, must be part of running a sanctuary.

M: Yes … my first losses were of two elderly ponies I took in. I just walked out to the field one morning and found one of them dead. As the first loss, that hit me very hard, and then a week later I found the second one dead in the field – it must indicate the strength of the link between them. But in retrospect, those deaths were an absolute blessing; I hadn’t had to intervene. (It took me back to the death of my dog Seamus a few years before – I was absolutely grief-stricken, and that tipped me over into becoming vegan.) Since then I’ve had to have cows put to sleep because they were old and ill, and I researched thoroughly to find the least traumatic way of doing it – I spoke to sanctuaries, I spoke to vets, and still had so many sleepless nights about it. The best way was to shoot them, and that’s what I’d been dreading the most, because of my army experience. I found someone who could do that, and although it was upsetting, he used a silencer and it was instant.

That was a big turning-point for me. I can’t shy away from that responsibility, so I’ve come to accept that this has to happen sometimes and if I ensure that the end is as kind and stress-free as possible, I don’t feel as bad about it as I did at first. It’s as important as anything else I do here, and I have to be at peace with that.

L: A bit about your background - what led you to veganism, and when? Your background (a farming and shooting family; a spell in the army) could have led you in a very different direction ...

M: I went to boarding school, and then the army. I think the key thing was trying to get my head around the fact that I was gay, and I became good at hiding that. It was illegal at that time to be gay in the army so I got used to playing a role that hid it very well, along the way developing confidence and quite a powerful ego. Then I became an actor, and part of the London gay scene; I got involved with recreational drugs, and developed a drinking problem too.

So a lot happened between the ages of 21 and 35, but it was ultimately quite self-destructive. I was struggling, and reached a critical point really – I was either going to go under, or find a way out, to heal myself. The teaching of acting was a big part of that, nurturing the ability to connect with others. When I came back to the countryside, aged 40, to get away from the madness of London, I just started to feel at home there, to see things differently and to connect. I started to play music, to grow vegetables, to have this connection with the earth. I got my dog Seamus, my cat Jack, and pretty soon I stopped eating meat, though it took me a bit longer to go vegan. I saw animals in a different way; I saw the cruelty, I saw the suffering, the things I hadn’t noticed before.

I now lead quite a monastic life here. I think my perception, the meaning of my life, is about service, and it’s about nurturing. The one thing that separates us from other sentient animals is this sense of choice. We’ve been gifted with the ability to notice suffering, and beauty, and our choice is what we do about that. If I’m not exercising that choice every single day I’m not being fully human.

L: There's an urgent need to reduce meat consumption overall - to reduce carbon and methane emissions, cut nature loss, to use less land and water, to reduce overuse of antibiotics on farmed animals, and to benefit human health too. And that's besides the animal cruelty on a barely imaginable scale that's well hidden by the meat industry. Do you think this message, about shifting our diets, is getting through to the public? Will behavioural shifts be enough to reduce meat consumption, or will it take government intervention?

M: I believe we’re a lot more vulnerable than we like to think. Everything about the way society has evolved has led to us shunning our vulnerability and becoming self-serving, with a false sense of security. Most people are unable to pull back from that. We can try to influence individuals, but so many people who essentially agree with us won’t do anything about it. It has to be a governmental shift, in our relationships with money, with power. For real change I think there has to be some seismic event that will really shift the way we think and lead to top-level decisions being made.

Meanwhile we can only influence individuals and try not to get too overwhelmed. We can only hope that things will shift in a direction that’s kinder. There’s that Tolstoy quotation “As long as slaughterhouses exist, there will always be battlefields” - I think we’ve just got to nurture kindness and compassion in every way we can.

There’s a power that comes through people meeting these animals here. We need more sanctuaries!

L: How do you see ways to use your sanctuary to engage with people?

M: We’re now a charity, trying to set up possibilities for that to happen more. My first priority is always to make the living conditions as good as they can possibly be for the animals, but alongside that I’m trying to set up the possibility of some kind of interaction with animals. Also, I’d like to bring people here for healing and meditation, that sort of thing. It’d be great to set up a tepee and have sharing circles. By association, if people come here for their own benefit they’ll see animals here that aren’t going to be killed for meat, and realise that it’s part of the peace of the place.

Alongside these things I’m trying to write a book, with the aid of journalist Claire Hamlett, and someone’s thinking of making a documentary about my life. If those things happen they could lead to more opportunities for outreach, talks and suchlike, involving more people. It’s all about getting the message out, having a voice. But first, I’ve got a sheep shelter to build!

L: Thanks so much, Mark, for giving your time to this discussion. It’ll be great to see how things develop, and I’m looking forward to the book!

To find out more about Mark and his animals, or to make a donation, see his regular posts on Facebook and Instagram, or visit www.amberwoodanimals.com.

A tribute to Aidan Chambers, 1934 - 2025

"A quiet trailblazer, always innovative with structure, bold and provocative ..."

Aidan Chambers is known and widely respected for his ground-breaking youth fiction and also as an educationalist with a special interest in how children/teenagers and books interact. With his wife Nancy he founded Signal, a review of children's literature, for which they were jointly given the Eleanor Farjeon Award, and from 2003-2006 he was President of the School Library Association. He has an international reputation and was a winner of the Hans Andersen Award, the Carnegie Medal and the Michael Prinz Award - the two latter for Postcards from No Man's Land. Aidan died on May 11th.

My friend Celia Rees and I, both great admirers of Aidan Chambers, wrote this tribute together. It appeared on Writers Review the week after his death.

Linda: I wish I'd been able to read Aidan Chambers as a teenager, which certainly isn't to say that I haven't loved his books as an adult - they're enduring favourites. But had I read them when younger, I'd have been enlightened and reassured, discovering myself in his characters and situations. He was a quiet trailblazer, always innovative with structure, bold and provocative for those readers who found and engaged with his work, while never a publicity-seeker. Dance on my Grave was one of the first teenage novels about homosexuality, without ever trumpeting itself as such; Postcards from No Man's Land included the now very topical subject of assisted dying. Neither, though, could be described as 'issues' fiction; he would rightly have resisted such categorisation.

In spite of winning the Carnegie Medal for Postcards from No Man's Land, he was better known and appreciated in other European countries than in the UK. In the days when I was frequently in secondary schools, I regularly recommended his books, disappointed that so few teenagers knew of them - though there'd often be a teacher or librarian nodding in agreement. It was notable that reports of his death last week appeared more quickly in the Netherlands, Sweden and Italy than they did here. While never really on the festivals or author tour circuits, Aidan travelled widely to speak at conferences, where he was admired as much for his writing about children and reading as for his ground-breaking fiction. In recent years he'd given up being traditionally published, but still wrote prolifically - how could he not? - producing privately-printed fiction and memoir which he sent out to friends and acquaintances. I was honoured to be one of those, and my collection of these books has pride of place on my shelves.

In The Age Between, he writes that youth fictions (his preferred term) "too often concentrate only on emotionally and physically sensational episodes, and neglect those other key aspects of youthhood which interest me the most and interests many youths: the cognitive, linguistic, and intellectual, the rich experience of fecund language and complex thought and spiritual awakening that are an important - I'd say vital - part of youthhood." These qualities are found in abundance in all his novels, never more so than in the one that remains my favourite, The Toll Bridge - cleverly structured, engrossing us in the lives of three characters, Jan, Tess and Adam (none of these their real names) linked by a physical and symbolic bridge and by the idea of Janus, who looks both forward and back. Brilliant, powerful, inevitably a bit dated but as fresh and vital as when I first read it in 1992, it gives the exhilarating sense of engaging with a mind that's constantly alert and agile, searching for meaning and identity.

Aidan Chambers set the bar very high, showing just how complex and satisfying youth fiction can be. He's inspired and influenced many a writer, including both Celia and myself. The book of mine that probably owes the most to him is The Shell House - which I dedicated to him rather cryptically. ('The other AC' is because one of the novel's characters also had those initials.)

Celia: Periodically, I read in the review columns of newspapers, the pages of The Bookseller, or on a blog post, or I hear on a podcast, bookcast or a book programme that ‘there were no YA novels before ---'. You can fill in the date. I allow myself a wry smile and forgive the ignorance because I know that is not true. For me, the 1980s were the golden age of what we now know as YA Literature. The writers who were writing then were pioneering a genre that could, indeed, be counted as Literature with a capital L. They were writing novels with the all the rich complexity of adult fiction, on serious, provocative subjects, but they were writing for teenagers (which is was the term we used back then). Publishers had dedicated lists for Teen Fiction, separate from their Children’s Fiction. I know because I was teaching English in a comprehensive school and I was was always on the lookout for fiction that would challenge and stretch my students but would rivet them to a story that was not for children, not for adults, but for and about them. This is difficult, skilled writing, driven by a passion to deliver the very best to that most deserving but ill served group of readers - teenagers.

Aidan Chambers was one of a group of writers which included Alan Garner, Joan Lingard and American writers S.E. Hinton, Robert Cormier and Lois Duncan. Their writing was brave, innovative and

powerful. It stood up to literary analysis and study but remained consistently engaging. Their fiction could involve serious issues: rape, homosexuality, violence and abuse but ‘issues’ were

never central, they were part of the story, because the story mirrored real life.

I was a huge admirer of this cohort of writers. They directly inspired me to become a writer. I wanted to write the kind of books that they were writing. So that’s what I did. Many years after I

began writing, I had the pleasure of meeting Aidan at a School Library Association Conference and was able to tell him what an inspiration he'd been to me and how much of a debt I owed to

him.

Aidan Chambers was also known for his deep knowledge, criticism and his commentary on the state of children's literature. He and his wife, Nancy Chambers, were passionate about reading and the need for books that would enable young readers to become sophisticated readers of adult fiction. This is one of the reasons that he was so highly regarded abroad. It was also why I was such an admirer. One of my favourite books of his is Postcards From No Man’s Land. In this book he not only tackles serious and difficult issues, sexual ambiguity and identity, assisted dying, but plays with narrative structure and form in ways that are as edgy as the subject matter. In my own novel, The Wish House, I took courage from him to challenge what is possible, or even acceptable in YA literature. It was a risk. The Wish House was admired by some, hated by others. It was a risk Aidan Chambers knew well.

We both acknowledge the influence of Aidan Chambers in our work - in particular in Celia's The Wish House and my The Shell House.

Animal Advocate No.9: Lauren St John, author

Lauren on a Born Free dolphin rescue in Turkey.

Brought up in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), Lauren is an award-winning author for children and teenagers and an ambassador for the Born Free Foundation. Her upbringing on a farm close to a ‘game’ reserve, described in her memoir, Rainbow’s End, brought her close to iconic wild animals such as lions, elephants, leopards and giraffes. These early experiences have inspired her highly-acclaimed The White Giraffe and the series that follows, which combine thrilling adventures with a focus on the very real threats facing African wild animals. Lauren won a Blue Peter award with Dead Man’s Cove, the first of her Laura Marlin mystery series, and more recently has published horse stories including One Dollar Horse and her latest title, Finding Wonder. Find out more on Lauren’s website.

Linda: Your upbringing has given you wonderful experiences and insights to draw on in your books for young readers; I especially like the way Martine, newly-arrived, falls under the spell of the smells, sights and sounds of the African landscape, and of course the animals. How and when did you form the idea of writing The White Giraffe? Did you decide at once on the magical realism element of this and the stories that follow – Martine’s special gift and the sense that she is destined to save animals?

Lauren: The idea for The White Giraffe came to me completely out of the blue when I was walking through Greenwich in London, on my way to do Christmas shopping. An image of a girl riding a giraffe popped into my mind, instantly followed by the girl’s name: Martine. When I was growing up on a farm and game reserve in Africa, we actually had a pet giraffe called Jenny. I thought: Wouldn’t it be the coolest thing on earth if you could actually ride a giraffe? The whole story sort of poured into my mind. When I got home, I actually wrote it down and thought that one day I might write a book about it. When I was a child, my family were always rescuing and saving animals. One of the gifts I wanted most was the ability to heal animals from pain and suffering. I knew from the start that I wanted Martine to have that gift and that it would be her destiny.

Linda: On the Rhodesian farm of your childhood, you were encouraged to hunt wild animals and to see this as the norm, yet you turned against it (in a memorable episode in Rainbow’s End). At the time, was that seen as rebellious? Did you try to influence others to reject hunting?

Lauren: I only ever went out with my dad and a couple of other hunters once. In Zimbabwe, as in many other countries in the world, it’s seen as the norm and was always painted as something exciting. We’d only recently moved from a city suburb to the farm. The farmer’s son, who was about a year older than me (around nine), went along with the hunting party, so I went too. That night, I saw the reality of hunting in a way that has stayed with me all my life. This magnificent kudu, one of my favourite animals in the world, such a majestic, innocent, sacred being, went from being vividly alive to empty of life in the split second it took for one of the party to fire a shot. That was the last time I ever went with them.

In a strange way, I’m glad I saw it for myself and at such a young age. It made me determined to fight for animals in every way available to me. I began to do that pretty much straight away. When the owner of the farm refused to take his injured horse to the vet, and my dad insisted (possibly correctly) that it could be treated on the farm, I phoned the vet myself, aged about nine, and begged him to come to the farm and help the horse. Understandably, he wouldn’t come without the permission of the owner. From then on, I was determined to become a vet so that I could help animals on my own. I filled a wooden trunk with any veterinary supplies I could get my hands on and treated any animal I could. My proudest moment from living on that farm was saving a racehorse from colic. His name was Hemite. I recognised the symptoms from something I’d read in an Enid Blyton book!

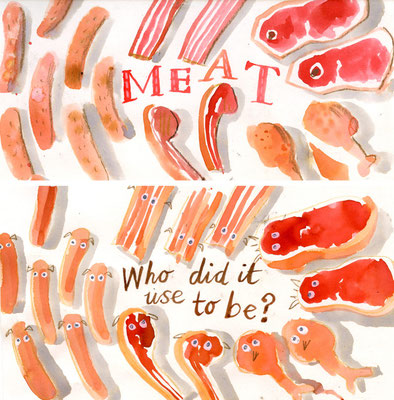

Linda: I like the fact that in several of your stories the main characters, e.g. Roo and her aunt Joni in Finding Wonder, are vegetarian, something you mention without drawing attention to it. (I think this is very important in fiction, helping to shift from the idea of meat-eating as the expected norm.) When did you become vegetarian yourself? Like most of us, you were brought up to eat meat – was there anything in particular that compelled you to change?

Lauren: Incredibly, my junior school took us to a slaughterhouse as a school outing when I was about 11. It was beyond horrific. That’s another experience that never left me. I didn’t eat any meat at all for ages after that, but it was difficult to become entirely vegetarian then because I was at boarding school from when I was seven until I was 15. They were government boarding schools, not posh ones, and the choice was extremely limited. I ended up eating piles of bread. I stopped eating meat entirely when I was about 22 because I was living in the UK by then and it was possible for me to make that choice. My book characters are purely fictional, obviously, but I always make the main character or two main characters, vegetarian. It’s incredibly important to me.

Linda: The Last Leopard includes an episode of ‘canned hunting’ (releasing a captured wild animal into an enclosure to be shot by someone who’s paid for the experience), horrifying Martine and her friend Ben. On social media we often see gut-wrenching photographs of people posing with wild animals they’ve killed – lions, zebras, bears, giraffes etc – and obviously feeling very proud of themselves. Sometimes it’s argued that trophy hunting (not necessarily canned hunting) has a conservation value, protecting habitats for many animals while allowing a few to be shot. What’s your view on this? Would you like to see laws strengthened, e.g. about the import of animal parts as trophies?

Lauren: Trophy hunters across the world like to position themselves as saviours of the wild to justify killing and maiming rare and precious creatures. However, in Africa statistics consistently prove that keystone species such as elephants, leopards and lions are worth considerably more alive – in terms of tourism, biodiversity and a thousand other things – than they are dead.

Since trophy hunting, by definition, is largely about ego, money, power and social media posturing, the hunters tend to want the special creatures – the elephants with the longest tusks, or the biggest lions or lionesses. If they kill the oldest elephants, they eradicate the experience that is critical for the survival of the herd. With all wild animals, survival knowledge is passed down. If they eradicate the biggest lions and lionesses, then frequently the remaining mate is not able to raise the cubs to adulthood because they can’t both hunt for food and keep them safe.

New laws are desperately needed to ban the import of animal trophies, but what is more desperately needed is the political will and police numbers to actually enforce even the existing laws. Look at fox and stag hunting in the UK, for instance. Theoretically banned, yet hunts across the country are killing and mutilating foxes and stags with impunity.

Linda: I absolutely agree about that, Lauren - hunts continue to commit wildlife crime, often in plain view. I hope we'll see an effective ban introduced to the UK in 2025.

Linda: You've mentioned you wish to help animals as a child, and that you usually had a collection of animals you were nurturing; your first job was as animal nurse at a vet’s. Was there a time when you seemed more likely to become a vet than a writer?

Lauren: I would have loved to be a vet but my high school wouldn’t allow me to take Physics and Chemistry, an essential entry requirement for veterinary school. I’m also hopeless at maths, so I’m not sure I’d have made the grade anyway. I did spend a year working as a veterinary nurse in Maidenhead, Berkshire, and that helped enormously when I came to write Kat Wolfe Investigates, because Kat’s mum is a vet. I think everything worked out for the best. I love writing so much.

Linda: I’m intrigued to read that your career as an author began with writing about golf and music (which seems an unusual combination!) How did that come about, and what prompted the change to writing for children?

Lauren: I left school when I was 16 and, as I've mentioned, started working as a trainee veterinary nurse when I was 17 in the UK. A year later, I returned to Zimbabwe and studied journalism. I got into golf while I was at college. After I graduated, I decided I wanted to be a sportswriter. Somehow, I ended up becoming The Sunday Times’ golf correspondent and following the men’s golf tour around the world for a few years. I’ve always been hugely into music, so when I left the tour, I spent a couple of years in and around Nashville and wrote a couple of books about American music. I had the best time, but I always longed to write fiction. I made a few attempts to write a novel, but they didn’t really work. The first idea I ever truly believed in was The White Giraffe. It was hard finding a publisher who felt the same way. It was rejected by numerous publishers over the course of nearly two years before it was published.

Linda: In your horse stories you combine elements of the traditional pony story with awareness of the exploitation of horses for money, selective breeding and competition success – Finding Wonder, another page-turning adventure, in some ways subverts reader expectations (no spoilers). Did your research for this story reveal elements of the ‘horse world’ that made you uneasy about the treatment of horses, and in particular of those that don’t make the grade?

Lauren: I’m a huge advocate of natural horsemanship and I’m deeply uneasy about many aspects of horse racing, showjumping and eventing, as well as the way some ordinary individuals treat their horses. Across the world, horses get a raw deal in millions of ways. At the same time, within all of those fields, there are many people who care passionately about the welfare, wellbeing and happiness of their horses. I don’t agree with all aspects of Monty Roberts’ methods, but I do think that Roberts began a conversation about horsemanship that has helped countless horses. In my writing, I try to reflect both sides of that and attempt to show small ways that might help make horses’ lives better.

Lauren with an orphaned rhinoceros in Zimbabwe, researching her book Operation Rhino.

Linda: Can you tell us about your role as ambassador for the Born Free Foundation?

Lauren: Working with Born Free is an honour and a joy. I’ve been with them on two major rescues. One involved relocating three leopards from a zoo in Cyprus to Born Free’s sanctuary in Shamwari. The other was to rescue two dolphins from a bankrupt dolphinarium in Turkey. Both rescues had a profound impact on me. It’s been amazing to witness their work firsthand over the years. Because so many of my books have conservation or animals as themes, we often work together on campaigns or projects. I’m doing a special World Book Day event with them in 2026.

Linda: You’re also a patron of Mane Chance, a sanctuary and charity founded by the actor Jenny Seagrove. How did you become involved, and what do you admire about its aims?

Lauren: Jenny Seagrove is a patron of Born Free, so we’d met a few times over the years. When I was writing my One Dollar Horse series, she asked me to give a talk at Mane Chance’s annual Christmas dinner. After that, she kindly invited me to be a patron, a huge honour. Mane Chance is the most incredible sanctuary. The way they transform traumatised and desperate horses, and give them happy, carefree lives, while at the same time helping those horses to help troubled young people, is truly inspirational.

Lauren with her childhood horse, Morning Star.

Linda: You started the campaigning organisation Authors for Oceans (of which I’m a supporter). What inspired this, and how did you set about starting up a campaign of your own?

Lauren: I was inspired to start Authors4Oceans after I ordered a soft drink in a book shop and it arrived with a plastic straw in it. Two things struck me. One was that, although I spent a lot of time talking to children about conservation, I hadn’t really considered the impact of the book industry – from book store cafes to book covers – on the plastic crisis worldwide. The second was that every single children’s author and illustrator I knew, yourself included, was extremely committed to saving our planet. I thought that if I contacted everyone we could maybe make a difference. It was astonishing how Authors4Oceans took off and how many publishers and bookstores changed their policy around plastic because of the campaign.

Lauren with a giraffe at a Harare sanctuary, Wild is Life.

Linda: I assume that as a highly-regarded author for children, you have many chances to talk to young people in schools and at festivals. Do you see this as an important part of your campaigning work?

Lauren: One of the best things about writing for young people is that children are so open-hearted. I enjoy visiting schools and going to festivals and seeing how fired up children are about saving our planet and about being better stewards of our earth than previous generations have been. I have high hopes for young people growing up now.

Linda: You’ve had the chance to see many magnificent animals in the wild. What would you say is one of your most memorable encounters?

Lauren: I feel incredibly fortunate to have seen some of the rarest and most special creatures on Earth in the wild. One of my favourite experiences ever was at a tented camp close to a huge waterhole in Hwange Game Reserve in Zimbabwe. Soon after I arrived, one of the guides came to say that four young bull elephants were close to the hide. We went into an underground hide and came up almost at their feet. I could see them silhouetted above me against the twilight sky. It was totally silent, and I could hear them breathing and drinking water. The entire time, they were affectionately wrapping their trunks around one another. At one point, they stopped and the four of them just leaned together and breathed. It was a bonding ritual. It was an unforgettable, almost spiritual moment and one that will stay with me all my life.

Linda: I know that your own companion animals are very important to you. Can you introduce them to us?

Lauren: Ever since I was a child, my animals have been my best friends. I adore my human friends, obviously, but the bond I’ve had with my closest companion animals over the years, starting with my Siamese kitten, Kim, when I was seven, has been one of the greatest gifts of my life. As a child, my Siamese Kim, my dog Tiger and my horses, Morning Star and Cassandra, brought my so much love and happiness.

Since I became a writer at 20, my cats have been just amazing, loving company. I adore my job, but as you know writing can be quite isolating at times, and it’s so incredible to have a cat on my desk all day and every day. My beloved rescue Bengal, Max, passed away last year at 17, after spending 15 years by my side. Now I have Skye, who is an Ocicat, and Teddy, another Bengal. They’re both very affectionate, but Skye sort of appointed herself as Max’s replacement. She’s incredibly sweet and loyal and follows me around the house like a shadow all day, every day.

Linda: Finally: anyone campaigning for animals and the environment has to find a balance between despair and optimism. How do you keep yourself motivated?

Lauren: I’ve been fortunate enough to spend a lot of time working with two of my animal heroes, Virginia McKenna and Jenny Seagrove. They had to bear witness to some of the worst examples of cruelty and destruction to nature and animals over the years, and yet they’ve remained hopeful and passionate throughout. They’ve inspired me to try to be the same way. The fight to save animals and nature is too important to give up on. Every single life – from the tiniest bee, ladybird, hedgehog and dunnock, to the largest whale or elephant is worth saving. Virginia McKenna believes passionately that every individual creature matters. I believe that too.

Linda: Thanks, Lauren, for sharing your views and experiences. I'm very envious of that elephant encounter! I hope you'll go on inspiring young readers, and adults too, for a long time to come.

Animal Advocate No.8: Jane Dalton, journalist

Jane Dalton writes for The Independent, where she's built up a reputation for exposing animal abuse in its various guises, and she's now a novelist, too.

She introduces herself:

'When I was in my early twenties and I started to become aware of various animal rights issues, my sister and I went vegetarian at the same time. To our delight, our parents were supportive and also gave up meat. My Dad, 92, is now semi-pescatarian, semi-vegan!

In my first job as a reporter, on the Dover Express, it was my Dad who encouraged me to write about the live exports he saw at the town's docks. I turned a feature into a fully fledged campaign against the trade, thanks to a supportive editor. Our team took a petition to Brussels and staged meetings and demonstrations at the port.

Later, my career included spells at the BBC, The Sunday Times, where I was Regional Editor, and The Daily and Sunday Telegraph. At The Telegraph, I wrote a review of a book about the unforgettable story of Judy, the dog who became a Second World War lifesaving hero - a book that moved me to tears.

After the Telegraph made its sub-editors, me included, redundant, I went back to reporting, and at The Independent have made animal welfare something of a specialism, albeit balanced with a wide variety of other news stories.

At some point along the way - I forget when - I became vegan. I haven't taken a flight for many years because of the climate.

I studied French and Russian at university but my languages are now rusty.'

Here Jane answers my questions.

Linda: Was there any particular animal issue, or any particular influence, that prompted you and your sister to become vegetarian in your twenties?

Jane: I know that when I was very young – maybe about seven – learning where leather came from was the most horrific thing I’d learnt in my life. My Mum was a passionate fundraiser for Save the Children, and we had cats (Siamese) when I was growing up, both of which were illustrations of our parents’ compassion. I think I sensed, too, that my Dad wasn’t keen on meat. As a student I told someone I was thinking of going veggie and he said, “But meat’s too nice to give up,” and I thought “Actually, no it’s not.”

Linda: Had it always been your intention to become a journalist?

Jane: No. As a girl, I wanted to become either a novelist or an architect, but was put off the latter by the seven years of training. I thought I could never be a journalist because I didn’t have the confidence and wouldn’t know the right questions to ask. Even after leaving university, I didn’t know what I was going to do. I then went on work experience to my local paper and they asked me back.

Linda: Working on the Dover Express, did you see first-hand the cruelties of live animal exports from the town docks? How did you go about launching your campaign? It's since been taken up by the RSPCA and by Compassion in World Farming - and has been a key campaign by CIWF, with backing from their high-profile supporters such as Joanna Lumley, Deborah Meaden and Peter Egan, and at last a ban on live exports from the UK has passed into law. That does show the power of campaigning, but also how much time and determination it takes for the law to change. There must have been times when you despaired that a ban would ever become reality?

Jane: I did, and the sight of the lorries crammed with living animals made me both incredibly angry and sad. I was extremely lucky to have an editor who was very supportive of our campaign – he seemed to know that it both would have the backing of readers and was also the right thing to do. We staged several demonstrations at the docks and held public meetings in the town to organise the next steps. Joanna Lumley was a supporter from the start – I remember meeting her at a protest outside Parliament once. You’re right – the ban on live exports does highlight the power of persistent campaigning. For a long time, successive governments blamed EU membership for their supposed inability to introduce a ban, so I did despair. So often, it seems those with the most power are the least willing to instigate change to prevent suffering. In the end, a ban on live exports was one of the few – if not the only - positive change(s) to emerge from Brexit.

Linda: With your varied and impressive experience in journalism, you now have an influential role at The Independent and have become an important voice in raising awareness of animal matters. Have you shaped that role for yourself, or was it something The Independent was particularly looking for?

Jane: The Independent definitely wasn’t looking for someone likeme. I shaped the role for myself, though I’m not sure how influential I am! I’m not able to devote all my working time to animal-welfare issues – I’m still needed for everyday general news coverage – but I like that. It helps keep me sane.

Linda: Do you have a fairly free rein at The Independent - can you cover any animal issue that comes to your attention?

Jane: No, I first have to pitch every story idea to the news editors for them to approve before I spend any time working on it. And ideas that aren’t strong enough don’t make it. But I don’t take the permission for granted – most newspapers and media outlets don’t do anything like the breadth of coverage that we do, so I’m appreciative of being able to expose animal-welfare horrors in between writing other general news stories.

Caption: pigs lying on concrete on an 'RSPCA Assured' farm. Photo credit: Animal Rising

Linda: You've covered important stories such as the recent exposures of cruelty on farms accredited by the RSPCA Assured scheme, and the links between rainforest destruction and crops such as soya imported to feed animals in this country, including those whose meat is stocked by major supermarkets and food outlets. In this role you really are in a position to raise awareness (and thank you!) Is there any story you feel has been particularly influential in this way - bringing something to readers' attention and beginning to change attitudes?

Jane: The stories exposing cruelty or neglect behind closed doors in slaughterhouses or on farms have the most impact on readers, it seems. The investigators who use hidden cameras or go undercover must take all the credit. I have enormous admiration and respect for people who have compassion for living beings yet choose to witness cruelty and torture like that. In some cases, supermarkets and the RSPCA have suspended suppliers based on those findings. It should mean the farms or abattoirs improve their practices – at least until the next time.

The story like that that got most attention was about goats being punched, hit, kicked and roughly treated at a big brand selling goat milk and cheese. It was the only time an animal-welfare story made our front-page splash, and I was interviewed on Radio 4’s PM programme about it. I’ve covered similar cruelty to pigs, chickens and cows, and the stories haven’t had the same coverage. I guess goats have more of a “cute” factor.

Linda: Most of us who campaign for animals are used to receiving hostility from people with vested interests, e.g. hunting and shooting supporters or meat-producing farmers - but in your role you're more prominent than most. Is this something you experience, and how does it affect you?

Jane: I’ve had a few comments on social media but luckily not too many. I am extremely careful about what I write on social media – I generally avoid using emotive language and I let the facts speak for themselves. I’m easily upset by criticism, unfortunately, and I don’t like confrontation so I don’t get involved in arguing online.

Caption: What's happening here? These are male chicks about to be ground up alive. This is the unseen price of eggs. Male chicks are surplus to requirements so are discarded. Does this sound 'humane'?

Linda: It's absolutely clear to anyone following the climate science that we have to reduce our dependence on animal agriculture - but still, to far too many people, any suggestion of cutting down on meat and dairy is seen as outrageous interference. Do you think there's any hope of shifting attitudes to food on the scale required, and quickly enough to avoid catastrophic climate change and nature loss?

Jane: This is an honest answer but not the done thing: At the moment, no – attitudes aren’t shifting anywhere near quickly enough. I think we’ll have to have more catastrophes such as late October’s dreadful flooding in Spain and/or some other seismic shift in policy by one of the world’s most influential powers before governments worldwide start adopting any changes serious enough to bring about change. I suspect it will have to involve carbon capture and storage alongside rapidly ending industrial factory farming and reducing flights.

Linda: Anyone who campaigns for animals can't avoid seeing gut-wrenching reports and images of cruelty. Is there something that particularly upsets you? How do you cope with that, and keep yourself motivated?

Jane: It’s a good question. We do it because it needs to be done, and thinking that I’m doing even a tiny little bit towards ending wrongdoing and suffering is rewarding. I can’t in all honesty say I enjoy discovering such horrific things but when I report on them, I try not to think about how it felt for that particular pig, fox, monkey, elephant or other creature. I think I close off that part of my brain to be able to cope.

Linda: Finally: your first novel, With Love from the Afterlife, will be published next year by Unbound - congratulations, and I'll look forward to reading it! What led to this venture into fiction - is it something you've always wanted to do? (And how did you find time for it alongside your day job ... ?) Are your animal and environmental concerns reflected in the attitudes of your fictional characters? Will this be a one-off, or are you already working on a second novel?

Jane: Thank you very much! I’d always wanted to write novels and started on my first one when I was eight. I wrote the bulk of With Love from the Afterlife while I was working and commuting full-time (I now work part-time from home) so goodness knows how I found time. I hardly ever cleaned the house and in the evenings I wrote instead of watching television. I also did a lot of editing during my commutes.

With Love from the Afterlife is about people, and is entirely separate from the issues I report on. However, there is one animal with a walk-on part – but you’ll have to read it to find out about that!

I’m working on a second novel, which is very different in style and subject matter from the first but I’m very excited about it. It’s very contemporary and linked to international current affairs but from an unusual point of view.

Linda: Thanks so much, Jane, for answering my questions. Keep on exposing these cruel realities, and good luck with the novel - we'll see you soon to talk about that over at Writers Review!

With Love from the Afterlife can be pre-ordered using this link.

A Tribute to K M Peyton, 1929 - 2023

It came as a sad shock to learn that K M (Kathleen Peyton has died aged 94, after a remarkable and distinguished career as a writer for both children and adults. Many readers love her Flambards quartet and the Pennington novels, and she's influenced many another author, including me - she was (possibly unintentionally) a pioneer of young adult fiction in the 70s and 80s, along with other such 'golden age' authors as Robert Cormier, Jill Paton Walsh, Jean Ure, Alan Garner, Robert Westall and Aidan Chambers. One of her extraordinary achievements was to publish books over eight decades - I wonder if there's another author in the world who can match that? Surely very few.

I first came across K M Peyton during my training as an English teacher, when I happened upon Flambards in the college library. I well remember how eagerly I devoured it, captivated by the setting, the characters, the social issues and how beautifully and economically she evoked countryside, seasons and weather. I went on to read more and more of her work. I'd always wanted to write, and she introduced me to young adult fiction, which hadn't existed in my own teenage years. So I owe her a great deal - especially as, many years later, she gave me permission to continue the Flambards story by writing a novel (The Key to Flambards) about Christina's great-great-granddaughter, set in 2018. I've written here about how I became friends with Kathy and about the various elements of the quartet that I wanted to pick up in my own story, so I won't repeat that here beyond explaining how we met: I was at the time a regular reviewer for Books for Keeps magazine, and asked to interview her for the Authorgraph feature. She invited me to her Essex home, and from then on we met regularly at publishers' parties or for lunch in Chelmsford, until she became less mobile and I visited her at home each year. A couple of times, staying overnight, I made a point of doing some writing in bed, in the hope that a little of the Peyton magic would get into my words.

Readers may not know that the M of K M Peyton referred to Kathy's husband Mike, an illustrator, writer and sailor. For a while they wrote serialised stories together, Mike supplying plot details while Kathy did the writing. Before that, Kathy had published her own first novel, The Horse from the Sea, when she was only 15; she once showed me her handwritten first draft of that story. She also showed me her MBE, awarded for services to children's literature, but I was more interested to see her Carnegie Medal - she won that for The Edge of the Cloud, the second of the Flambards books, as well as the Guardian Prize for the trilogy (as it was then). Other accolades include the Children's Book Award, for Darkling. Numerous other titles were shortlisted for the Carnegie and in 1966 she was declared runner-up for Thunder in the Sky, the year the judges decided not to award the Medal - she always retained a sense of aggrieved bemusement about that! (And in my opinion, Thunder in the Sky would have been a worthy winner.)

So what were the qualities in her writing that earned her such acclaim and such devotion from her readers?

David Fickling, editor of many of her books, has called her 'a born writer', and surely she was - with the desire to write from an early age, and an enviable gift of fluency that made writing look easy. In our conversations she told me that she didn't like revising her work, and only did so at the request of editors, sometimes reluctantly. She was described by John Rowe Townsend (I think it was him) as 'an Ancient Mariner of a storyteller' for her compelling plots. She was particularly good at action, whether it involved horses and hunting, early aviation, sailing or mountain-climbing - the finale of The Boy who Wasn't There is truly nail-biting. Her characters and the tensions among them were never less than compelling; she was attuned to adolescent yearnings, frustrations and conflicts, and several of her stories involved a young person at odds with a demanding or ambitious parent and determined to find their own way in life. And no one - not even Dick Francis or Cormac McCarthy - wrote about horses better than she did; their beauty, grace and vigour, their personalities.

(Erm, hunting. If you follow this blog, and especially if you've read my most recent Animal Advocate feature on Rob Pownall of Protect the Wild, you may be surprised that I could enjoy the Flambards books, especially Flambards itself and Flambards Divided, with their relish of fox-hunting. I'm a long-term supporter of the League Against Cruel Sports and now of Protect the Wild, and can't wait to see a complete ban. The Flambards books, however, depict fox-hunting in the past, which in my opinion is where it belongs.)

Meg Rosoff is another author who was impressed by the qualities of Kathy's work, writing in a Books for Keeps article: "I started reading and couldn’t stop. Something about this woman’s writing resonated directly with my brain and my heart – the unsentimental, sharply-observed, clear voiced love of horses and riders, the trials of adolescence, of friendship and country life and the endless difficulties with families, all rendered in the most intelligent elegant prose."

Best-known for the Flambards quartet and the Pennington stories (oh yes - she could write wonderfully about music, too; Patrick Pennington was a gifted pianist) Kathy wrote a number of stand-alones that were just as impressive. A favourite of mine - and, I know, of hers too - is A Pattern of Roses, a beautiful and lyrical mystery which begins when Tim, son of materialistic, class-conscious parents making a new life in the country, finds a gravestone with his own initials on it, marking the death of a fifteen-year-old boy from Edwardian times with whom he finds affinity. This book was filmed, incidentally giving the young Helena Bonham Carter her first screen role as the imperious, privileged Nettie. The cover shown here uses Kathy's own artwork - a trained artist, she provided cover images for several of her novels as well as illustrations for some younger books. Her painterly eye is apparent in her evocation of place, shown here just before Tim finds the other boy's grave:

He walked across the churchyard, through long yellowing grass. It tapered down to the compost heap, the elm-trees closing in on it. A few graves humped themselves untidily; it was the cheap end, Tim thought, the stones, roughly etched, all illegible now with lichen and time. There was a rose-bush growing, with strange, smoky-violet flowers dropping faded petals into the grass. The colour smouldered; the roses, the rotting peat round the gardener's heap, a tangle of old man's beard like white mist over the elm hedge. Tim saw it with his O-Level artist's eye, and smelt the old summer going and all the years and years that had gone before in the decayed, deserted corner of the churchyard.

The Flambards trilogy (as it was then - the fourth book, Flambards Divided, followed after an interval of twelve years) was filmed by Yorkshire television - it's well worth watching, but true Peyton lovers will prefer the novels. I still love, as I did back in my twenties, the sense of imminent change as the First World War approached; the feudalism of Uncle Russell and his obsession with hunting, the social inequities that Christina's cousin Will sees clearly. When the kindly groom Dick is unfairly dismissed by Uncle Russell and Christina visits him at home where he cares for his invalid mother, she contrasts the poverty there with the attention lavished on the Flambards horses:

She thought of the new blanket on Goldwillow that Dick had smoothed the last time she had seen him in the stable: thick and bright with stripes of black and red on deep yellow. The blankets she looked at now were grey and threadbare. Dick's mother was less than a Flambards horse. Dick had always known it. It was a part of his reserve, his quietness, knowing things like that, she thought.

Kathy hadn't at first intended Flambards to be published for children; it was at an editor's insistence that it appeared on a children's list, but as the series progressed to depict Christina in her twenties, widowed, divorced (sorry, spoilers) and contemplating a new beginning, it became what we would now call crossover fiction. Kathy wrote several adult novels too, though they never won acclaim to match her writing for young readers. The Sound of Distant Cheering is set in the world of horse-racing, clear-eyed enough to show the seamy, callous side of the industry alongside the glories and the triumphs: Jeremy, a trainer, thinks:

Oh, Jesus, who would be in the racing game! It was so magnificent at its best, seedy – to put it kindly – at the bottom. Human greed ruined it; the exploitation of one of the kindest, gamest animals on earth for money ...

Possibly her favourite of her adult novels was Dear Fred, set in Victorian Newmarket, in which teenage Laura is obsessed with the champion jockey Fred Archer before finding loves of her own. Kathy felt that this had been published rather uncertainly, not a children's book but not marketed for adult either; in recent years she hoped that it might be reissued, something we discussed. Anyone ...?

I will miss my visits. Kathy was always great company - forthright, sparky and funny. Sometimes we talked in her study, a spacious room overlooking the garden and her bird-feeders, with shelves lined with her own books among many others. On the walls were a number of fabric collages she had made, all depicting horses in her distinctive style. On warm days we would sit outside the back door looking out at the large pond, or walk into the wood she had planted alongside the house over many years - another commendable achievement.

She'd started another novel, for adults, in her nineties, but failing concentration halted its progress. It's sad to think that there will never be another K M Peyton book - but for her many admirers, or for those new to her work, there's that huge, glorious list of titles to revisit or discover for the first time, and the inspiration she's left to both readers and writers.

Animal Advocate No.7: Rob Pownall of Protect the Wild

Rob is the driving force behind Protect the Wild, which began as Keep the Ban. Still only 24, he's been campaigning against cruel sports since he was 15. Protect the Wild was voted Campaigner of the Year by Great Outdoors magazine and is influential in exposing cruelty and malpractice by hunts and shoots. One example is supporting the Mini's Law campaign after a cat was killed outside her home on a housing estate by a pack of hounds. Last year Protect the Wild issued a striking animation, A Trail of Lies, voiced by Chris Packham and showing the reality of 'trail hunting' - watch it here. Find out much more on the website, including information about wild animals and the law. If you'd like to join the campaign and receive regular newsletters and updates, everything you need is here.

Linda: Could you give a bit of background about how you got started on this? Were you aware of cruel sports as a child? Were you brought up in a rural area where you saw hunting and shooting? Were there other things such as books, documentaries or influential people that sent you in this direction?

Rob: My awareness of cruel pastimes such as fox hunting and bird shooting was fairly limited as a child. It’s only when I look back now that I realise in hindsight that up until the age of 16 I was very much living in a bubble, isolated from not just issues of wildlife persecution but all forms of animal abuse. It wasn’t until I came across an online petition aimed towards preventing David Cameron from repealing the ban on fox hunting that I became aware of the fact people were still hunting foxes with packs of hounds.

And it’s for this very reason that I always remain strong willed that petitions can make a difference even if they can often feel powerless in achieving change. Because from this petition I opened my eyes to what was happening. I watched videos, read articles, joined online groups, and within a couple of weeks the Keep the Ban page was born out of a desire to end the madness that was unfolding.

Linda: Your single-mindedness on this campaign is impressive and is already seeing results. With so many other kinds of widespread cruelty to animals around us, for instance in intensive farming, why is it this campaign you've decided to devote yourself to?

Rob: Single-mindedness is vital to stay focused and achieve success both in the short and long term. But it’s certainly challenging at times keeping to this philosophy in the face of so much cruelty inflicted on animals in so many other areas. Especially with a platform to promote and put a spotlight on other forms of cruelty taking place.

And like many other campaigners we always get the same old retorts of ‘what about x?’ The reality is we can’t cover everything, and if we tried to do so we would only water down our central focus and dilute the message of protecting British wildlife.

There are some brilliant groups and people advocating to end the animal agriculture industry, for example, but it’s not Protect the Wild’s fight. However, as time passes it becomes ever more apparent that wildlife persecution and the animal agriculture industry have considerable overlap.

You’ve only got to look behind the reasons for the badger cull in protecting cattle that are then exploited and slaughtered for human consumption. On a personal level I’ve been vegan for six years now. And unlike many others in the wildlife protection movement I’m not a speciesist, fighting for one animal to be protected whilst paying for other animals to be killed on my behalf.

As far as I’m aware, Protect the Wild is the only wildlife protection organisation ran with vegan principles and advocating for all life to be conserved, not just wild life.

And from where I see it, we'll only see the end of animal agriculture if we can create a shift in societal thinking. If the notion that some people can hunt wild animals for enjoyment still persists, then how on earth will we ever persuade the public they shouldn’t be consuming animals too?

Linda: I listened to your interview on Off the Leash podcasts with Charlie Moores, and was impressed by your determination and clarity. What are your immediate aims for Protect the Wild - where do you see progress happening most imminently?

Rob: It's my belief that wildlife persecution is one of the major dominoes that needs to be knocked down to further the animal rights movement as a whole. Once it topples and we see the end of pastimes such as fox hunting then naturally people will begin to shift their thinking towards other forms of animal abuse. If we can destroy societal acceptance for bloodsports, we will be well on our way to protecting all animals from abuse and exploitation.

But when it comes to Protect the Wild’s immediate aims, our focus is a lot more short term. To be honest the situation is pretty dire when it comes to wildlife abuse across the UK. We’re under a Government that couldn’t care less about these issues or doing anything to help end them. And the vast majority of laws supposedly protecting wild animals are falling way short of the mark. And that’s why over the next year or so we see educating the public and directly helping activists in the field as the best way forward. While we still have overarching goals for legislative change, our current aims are to do absolutely everything we can to equip activists and shape public opinion until a change of Government during the next 18 months.

Linda: Protect the Wild, the League Against Cruel Sports and various hunt monitor groups are doing great work in recording and filming hunt trespasses and illegal activity, and have achieved high-profile coverage and prosecutions for cruelty - the sort of things that have always gone on out of sight of the public, such as digging out foxes and throwing them to hounds. Yet hunts can still claim that they're following trails and that kills are 'accidental'. Clearly the 2004 Hunting Act is inadequate - what do you think are the prospects of a complete ban on hunting with packs of hounds?

Rob: This potential Government change could prove pivotal in whether we get a proper ban on hunting or not. As I've already mentioned, there's no hope for any legislative change as things stand - it's not pessimistic or defeatist to admit that when it’s the reality of the situation. But what we should be doing is advocating for a new proper ban on hunting in this year or so before the next election. What we shouldn’t be doing is campaigning for the current flawed ban to be strengthened. It’s no good fiddling around with an Act that is littered with exemptions and loopholes. It only opens up the goal for the pro-hunt lobby to sneak in one modification or amendment that could send us back to square one.

You’d have to ask the groups forming the coalition for strengthening the Hunting Act why they genuinely believe this is a better approach for wildlife than fighting for the ultimate goal, a new proper ban similar to that of Scotland’s that would unequivocally end this madness for good.

But it’s not just the campaign for legislative change that will end fox hunting. The pastime will die from a thousand cuts coming at it from multiple angles. And I'm a firm believer that a mixture of finances, insurance issues, hunt arrogance and public pressure will be the perfect mixture.

Linda: Around where I live, in Oxfordshire, there are regular reports of hunts trespassing on roads, private property and even on railway lines, endangering the public as well as farm animals and domestic pets. I wonder if eventually it will be episodes like these, rather than cruelty to wild animals, that lead to a ban on hunting with hounds?

Rob: Specifically, hunts have long been running roughshod across the countryside, recklessly crossing roads, and killing hounds and endangering the public in the process.

Now this is where it gets interesting. The vast majority of hunts are businesses and should be subject to the same health and safety regulations as all other businesses. But up until this point the HSE (Health and Safety Executive) has refused to treat hunts like other businesses.

But if they were to be, then a hunt would be held liable and senior members of the hunt could face huge fines and imprisonment if they caused an accident or injured a member of the public. Protect the Wild is leading the campaign to ensure hunts are treated as businesses by the HSE and this could be a game changer. These arrogant gangs have for too long gotten away with being treated differently to the rest of society. They’re not above the law or regulations and it’s about time they were reminded of this fact.

Ironically the underlying preference towards human life over animal life may be what leads to the downfall of hunting. As much as moral sentiments are shifting, we need to focus just as much attention on the human impact too. If laws and mainstream thought is so centred around the value of human life and the human experience, we should utilise this to our advantage. We will use every single angle possible to achieve our aims and hunt havoc is a key one - it’s time for these hunts to be bogged down in paperwork and checks just like every other business.

Linda: Are you attracting personal enmity through your campaigning, and do you see this as a risk? Chris Packham is regularly targeted on social media and even at his home in unpleasant and threatening ways because of his outspokenness on hunting and shooting. Have you experienced anything like this, and if so, how do you deal with it?

Rob: As a result of our determination and desire to say it how it is, I fully expect to encounter more personal issues. There's one incident I haven’t publicly spoken about before. About a year ago, police arrived at my home because someone had called in to say I was dead, an experience I wouldn’t wish on anyone. Whether this was connected to my work I can't be sure, but it's more than probable.

But when these things happen you know it's because you’re doing something right and this is how I remain firm in my convictions. There will always be personal risks with anything we do in life and I’m just happy that we’re on the right side of history.

Linda: I'm glad to be interviewing you now, at the start of the 'autumn hunting' season, which as we well know is cub-hunting exactly as it was carried out before the 2004 Hunting Act. How do hunts continue to get away with this? Surely it gives the lie to the whole concept of 'trail-hunting', its purpose being to introduce hounds to the scent of fox. And well done for highlighting it!

Rob: ‘Autumn hunting’ or ‘cubbing’ season, from late July until the start of November, is a vile and barbaric activity. What’s even worse is how few people are aware it even goes on. It involves a hunt surrounding a wooded area or crop field, usually in the early hours of the morning and sending hounds in to seek out and kill fox cubs. This is done to train the hounds to kill prior to the main hunting season. And of course it completely dismantles the ‘trail hunting’ sham. If hunts were indeed following an artificial trail as opposed to a live mammal, this vile practice wouldn’t be happening.

The issue is that, for obvious reasons, it's so hard to film and capture evidence of cubbing, with hounds entering covered terrain. That's why we produced our video The World’s Worst Sport to shine a light on this activity. In the meantime hunts continue to get away with it. It’s hard to police and there's a lack of public knowledge of it happening, so fewer people are reporting suspicious activity. If we had a proper ban on all hunting with hounds, this would end cubbing overnight.

Linda: Protect the Wild also campaigns against shooting, and here too the contentious issues are becoming more widely-known: the burning of vegetation to benefit grouse-shooting; the poisoning and baiting of birds of prey such as hen-harriers and eagles on shooting estates. The campaign here is up against power, wealth and vested interest and will possibly be a harder one to win. How and where do you see the potential for change?

Rob: When it comes to the shooting industry it’s almost a whole different ball game from that of ending hunting. Until a year ago we'd always been a single issue organisation and as such the vast majority of our supporters are anti-hunting but not necessarily anti-shooting.

This poses us with a challenge of educating our existing supporters and the wider general public. And this challenge is harder because the shooting industry is stronger, better funded and even more protected than the hunting industry. And speciesism means more people care about fluffy mammals than they do about birds and we need to acknowledge that. We first need to get people to care about birds and what happens to them before we can tackle the industry itself.

Indeed we're on a major education drive to actually get across what is happening across the UK. Bird shooting involves millions of different birds being blasted out of the sky for fun, but it also has huge consequences for the environment and other animals. From pollution of water sources and the burning of grouse moors to the snaring of foxes and killing of birds of prey, these are issues that extend beyond the morally repugnant act of killing a bird. If we're to end shooting then we first need to ensure the public are aware of why it should be ended and the arguments we're putting forward.

Logically our next step will be to slowly push our legislative demands to an audience that has a greater understanding of the issue. We will also ensure our Protectors of the Wild initiative makes it as easy as possible for members of the public to identify and report suspicious activity linked to shooting. Media campaigns will also prove vital in getting the message out there, something we did with considerable success at the beginning of the year. 1.6 million people have now viewed our animation exposing the victims of the shooting industry. And of course we'll continue to expose the realities of what happens on shooting estates - we’ve so far supported several undercover investigations.

Linda: At just 24 you're at the beginning of your career. How would you like it to develop - what are your ambitions? (other than seeing an end to bloodsports, of course!)

Rob: My personal ambitions, aside from ending hunting, shooting and all forms of wildlife persecution (there are way too many!) are to make a difference and help those who can’t speak out for themselves. I’m a firm believer that anything can be achieved when you dedicate yourself to a particular goal. I’ll always be fighting for animals but I hope to see a day where I don’t have to. It’s hard to look too far ahead because I think I’ve only just started.

Linda: Thanks so much for this, Rob, and for all you're doing to change attitudes and to eliminate cruel sports from our countryside. All power to you and your campaign!

The Great Big Green Week

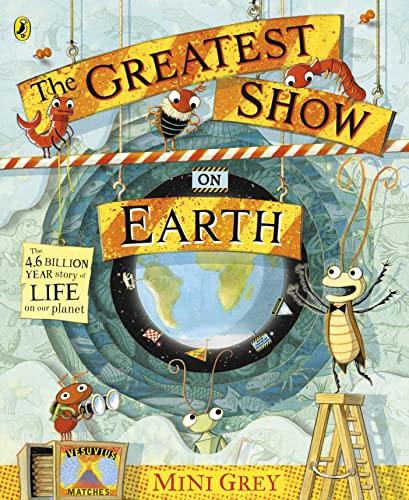

I'd like to think that all my books have green awareness in their DNA, but for The Great Big Green Week, which runs from 10th - 18th June this year, here are four that I'd like to focus on.

Lob brings the timeless figure of the Green Man into the modern world - as Lob, the unseen garden helper of Lucy's Grandpa Will. Lucy longs and longs to be one of the special people who can see Lob - but when Grandpa's cottage is put up for sale, and Lob must take to the roads in search of his next place to stay, Lucy thinks she's lost him for ever ...

'A deep sense of the passage of the seasons .. a love song to imagining, understanding, breathing and living in harmony with the natural world.' Kevin Crossley-Holland

For age 7+. Copies can be ordered here from

Bookshop.org.

The Treasure House was inspired by my experiences as volunteer in a charity shop and my realisation that the shop served as a kind of sanctuary for some of its customers and volunteers.

When Nina's Mum suddenly and inexplicably disappears, Nina finds clues, solace and new friendships at the charity shop run by her great-aunts. There's much about community support, kindness and empathy - and the fun of upcycling!

"Linda Newbery vividly creates the atmosphere of a delightfully shabby second hand shop full of intriguing treasures and idiosyncratic customers, in this charming story." Booktrust

For age about 10+. Copies can be ordered here from Bookshop.org.

There's much more upcycling in Rubbish? - a look at things we might throw away (but there is no away!) and what we could turn them into, with a bit of imagination, sharing and adult help. Join the children of Kingfisher Class as they turn pine cones into owls, old tyres into strawberry planters, socks into puppets and more. Charmingly illustrated by Katie Rewse.

For age about 3+. Copies can be ordered here from Bookshop.org.

Whether or not we think of ourselves as animal lovers, the choices we make every day - what we eat, buy, wear, use, waste and throw away - affect animals and the environment. Here are ways to make animal awareness part of our lives, and to reduce our impact on the planet's resources. Live kindly, tread lightly!

'This is the book we all need right now.' Children's Books Ireland

For teenagers and adults. Copies can be ordered here from Bookshop.org

The Great Big Green Week is the UK's biggest ever celebration of community action to tackle climate change and protect nature.

From festivals to football matches, litter picks to letter-writing - there's something for everyone at the Great Big Green Week. What's going on near you? Find out more here!

Silent Earth: Dave Goulson

Dave Goulson is Professor of Biology at University of Sussex, specialising in bee ecology. He has published more than 300 scientific articles on the ecology and conservation of bumblebees and other insects. He is the author of Bumblebees: Their Behaviour, Ecology and Conservation; A Sting in the Tale, a popular science book about bumble bees; and other titles including The Garden Jungle and Gardening for Bumblebees.

He founded the Bumblebee Conservation Trust and is a trustee of Pesticide Action Network and Ambassador for the UK Wildlife Trusts. In 2015 he was ranked at No.8 in BBC Wildlife Magazine’s list of the most influential people in conservation. (Picured: Dave Goulson speaking at The Big One at Westminster, April 2023. Photograph by Linda Newbery.)

“One of the penalties of an ecological education is that one lives alone in a world of wounds", wrote the American conservationist Aldo Leopold in A Sand County Almanac. Not so much alone now as Leopold must have felt in 1949; 'climate grief'' and 'eco-anxiety' are now widely-used terms which have their own Wikipedia entry.

Dave Goulson's book, subtitled Averting the Insect Apocalypse and referencing of course Rachel Carson's seminal 1962 book Silent Spring, won't exactly help sufferers to feel more confidence in the future of wildlife and biodiversity (how could it?) but is nonetheless appealing and informative. I both read and listened - the audio version is engagingly read by Goulson himself. I heard him speak at the Chipping Norton Literary Festival last year, where he related an anecdote that appears early in this book. Asked at short notice to be interviewed for Australian radio (from a men's loo - the quietest place he could find in the pub where he happened to be eating a meal) he was confronted with the opener: "So - insects are disappearing. That's a good thing, isn't it?"

Unfortunately, that question reflects the view of a great many people who see insects only as bothersome pests, biters and stingers, unwelcome invaders of homes and gardens and spreaders of disease. But, as the biologist E O Wilson has written, "If all mankind were to disappear, the world would regenerate back to the rich state of equilibrium that existed ten thousand years ago. If insects were to vanish, the environment would collapse into chaos." Even if we're incapable of valuing wild creatures for themselves and not merely for how they can serve us as pollinators, ecosystem managers or food, we're taking huge risks with our careless approach that creates such drastic losses.

Goulson examines the complex relationships between insects and ecosystems and how drastically these can be affected by human interventions. The chapters on neonicotinoids and glyphosate are particularly shocking, revealing how university-based, peer-reviewed studies were challenged and in the end overpowered by the interests of Big Business. I was dismayed, too, to learn that flea treatments readily available for dogs and cats (including Frontline, which I've been using for my cats) contain neonicotinoids.With dogs in particular, there's a risk that swimming in rivers can release neonicotinoids into the water, with dire effects on aquatic wildlife. Glyphosate is widely used by councils and elsewhere to suppress weeds, so even though the World Health Organisation's International Agency for Research on Cancer stated in 2015 that it's 'probably carcinogenic to humans', most of us probably have it in our bodies. This conclusion was countered by safety evaluations commissioned by Monsanto, the manufacturers, which came to a different conclusion. Who would we rather believe, and who should we believe? "Allowing companies to evaluate the safety of their own chemicals remains standard practice around the world," Goulson writes, "despite the obvious conflict of interest that this creates." He also points out that chemicals are tested in isolation, it being impractical to run controlled experiments on the cocktail of pesticides insects and plants are regularly exposed to, to investigate what cumulative harm might be caused.

I share Dave Goulson's frustration that toxic chemicals are displayed in garden centres and supermarkets everywhere, with names like Bug Clear encouraging consumers to see all insects as dirty, dangerous nuisances and to spray their gardens indiscriminately. The campaign group Pesticides Action Network, of which Goulson is a trustee, pressures retailers to stop stocking harmful toxins, with some success: in the UK, Waitrose and the Co-Op have made recent commitments to remove these products from their shelves; this April, the Royal Horticultural Society has just issued a statement that it will no longer refer to slugs, beetles etc as 'pests', and will stop selling insecticides in its shops.