I'm hoping to make this a regular feature here - interviewing people who campaign for animals in a range of ways. I'm delighted that Gill Lewis has kindly agreed to be my first guest.

Gill is a wonderful writer for young readers, many of her stories drawing on her experience as a vet and her travels to see wildlife in many countries. From her first novel, Sky Hawk, to her most recent, A Street Dog Named Pup, her books are thoroughly absorbing. There is always an animal ingredient, ranging from outrage at the poisoning of golden eagles on a shooting estate and the anxiety of following a tracked osprey on her flight to Africa and back, to the perils faced by the abandoned Pup on the London streets and the dependence of an exiled woman on her collection of birds. There's also a sense of wonder at the beauty of the natural world and its inhabitants. The humans in Gill's stories are equally important, with sympathetic portrayals of Eritrean refugees in The Closest Thing to Flying, the struggles of Scarlet to keep her family together against all odds in The Scarlet Ibis, and many more.

A Street Dog Named Pup is already on my Books of the Year list! I haven't read all her books, but after reading several I know that she's an author you can depend on for a gripping story that will thoroughly involve you in her characters' worlds and the dilemmas they face.

Here she answers my questions about her writing and her campaigning for animals.

L: For A Street Dog Named Pup, did you consciously have Black Beauty as your model – I mean in terms of the episodic structure and the rise and fall of Pup’s fortunes depending on the people he comes into contact with?

G: I didn’t consciously have Black Beauty as a model for the story, although I did want the story to span the lifetime of Pup. That isn’t to say my subconscious might have been working very hard at this! I loved Black Beauty as a child, and as an adult I researched Anna Sewell for an essay about anthropomorphism and discovered that her story helped raise awareness about the welfare of horses.

L: Through the various dogs Pup meets in the Railway Den, you introduce a range of topics of concern without being at all heavy-handed: puppy-farming, dog-fighting, ear-cropping, irresponsible pet-owning, ‘handbag dogs’. What would you like young readers to take from the book?

G: Ultimately, the story is one about the unique bond that we can have with dogs, about loyalty and trust and dogs’ unconditional love. I hope the story enables young readers to see the world through dogs’ eyes, and to understand their physical and emotional needs. I would love young readers to understand the concerns of canine welfare and in doing so raise awareness of responsible dog ownership.

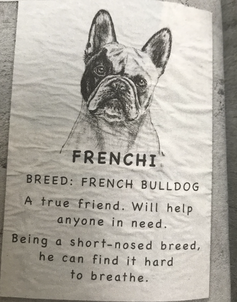

L: I know that your work as a vet has made you particularly aware of the problems for dogs selectively bred to have flat faces (brachycephalic breeds such as pugs, bulldogs and French bulldogs like Frenchi in Street Dog) – these dogs often have serious breathing difficulties. Yet those breeds seem increasingly popular. Do you blame fashion for that – and if so, what can be done to discourage the trend?

G: The rise in brachycephalic breeds as pets and their associated health problems is the biggest companion animal welfare problem at the moment. Their popularity is driven by their cute face, which has much resemblance to a human baby – button nose and big eyes. Celebrities owning these dogs have increased the demand for them. But the grim reality for these dogs is that they are literally dying to breathe. They have shortened noses but have excess skin around their face and also excess soft tissue inside the nose and throat that obstructs breathing and eating. Many owners don’t recognise the signs of disease; such as excessive snoring, persistent tiredness and holding a toy in their mouth whilst sleeping to keep the airway open. Indeed, many of these signs of disease are seen as endearing. Dog food companies are changing the shape of the dog biscuit, so these dogs do not choke on their food whilst swallowing. We should be changing the shape of the dog, not the shape of the food. The British Veterinary Association runs a campaign to prevent the use of brachycephalic breeds in advertising. I believe we need to raise this awareness across society to enable children and adults to make informed choices. The pug breed is very commonly portrayed in children’s books, for the very reason that it is so childlike, but I believe publishers have duty to follow the British Veterinary Association guidelines and not use these breeds in children’s literature. I did pose the question on Twitter and was met with tumbleweed silence from the publishing world. Maybe no one from publishing noticed, or maybe pugs are just too marketable as a money-spinner. I would defy anyone to spend a day at a referral clinic for Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome and not change their mind.

L: The dog-fighting scenes in A Street Dog Named Pup are particularly harrowing (even for someone of my age who already knows how cruel it is!) Did you ever come into contact with victims of dog-fighting during your time as a vet? Did you find those scenes hard to write?

G: These scenes were really hard to write. As a vet I never came into contact with the victims of dog fights, because the people who run dog fighting would never consider taking a dog to the vet. However, I did speak to a friend who works in the police to find out about the criminal gangs who keep and breed dogs for fighting. I didn’t think I could be easily shocked but some of the cruelty is beyond belief.

L: How can people (even, or especially, those who love animals) be discouraged from supporting tourist attractions such as dolphinariums, roadside zoos where visitors can pose with tiger cubs, and the like?

G: I remember when I was young, I was at Blackpool with a friend and we wanted to see the dolphin show. As an animal-mad child, I wanted to be up close and personal with such a charismatic creature. I’d watched Flipper on TV and harboured secret thoughts of swimming with dolphins. So, we paid to see the show. So I understand why people want tiger experiences, or visits to dolphinariums. It’s often a chance to see these incredible creatures close up and be in awe of them. But I remember that trip to Blackpool, and the reality of watching a dolphin in a tiny pool, going round and round and round. It had sores on its skin and it looked visibly depressed. My friend and I felt very sorry for it. I think if there had been a campaign at the time raising awareness about the dolphin, that we would not have paid our money and watched the show. Raising awareness is key, to show the mental and physical suffering and the impact on the environment of animals poached from the wild. Social media can help spread the work and raising awareness on some travel tourist sites like Trip Advisor can have a big impact.

L: When you began to write fiction, did you immediately see it as a way into campaigning with young people? Or has your work with Hen Harrier Day, Wild Justice and other organisations grown out of the writing, as people came to know and appreciate your books?

G: When I started writing, I followed the advice about write what you love, and for me that was writing about animals and wild places and our human connection with them. My first book was Sky Hawk,, a story about an osprey connecting children in different countries. I didn’t intentionally start writing as a way into campaigning, but as my writing journey progressed, and I spoke with many people about concerns of the planet, I found my own voice to speak about these things. I feel privileged to know many other creatives: Jackie Morris, Nicola Davies, Lauren St John, Dara McAnulty and Piers Torday, who use art and story to raise awareness and empower others to make a difference too.

My involvement with Hen Harrier Action and Wild Justice is to be another voice calling for change. The UN has declared the next decade as the one of rewilding. We have to change our upland land use from monoculture managed heather to a restored landscape of many habitats.

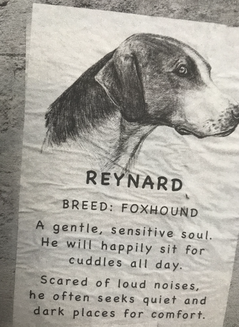

L: Your books are critical of hunting and shooting, and the management of shooting estates that so often involves the trapping or poisoning of birds of prey, such as eagles and hen harriers. I liked your inclusion in Pup of Reynard, a foxhound who narrowly escaped being shot because he wouldn’t hunt foxes so was no use to the pack – one aspect of fox-hunting we don’t hear much about. Have you had any criticism from supporters of these ‘sports’?

G: I have had criticism from the driven grouse shooting community, but I have researched this area so thoroughly from both sides of the debate that I can counter their arguments with facts and science. Most of the debate has been civil, although there are some abusive keyboard warriors out there who often seem to take umbrage, especially when a woman has something to say.

Some of the criticism has been from a minority of conservationists who feel some of my comments are outspoken about driven grouse shooting. I firmly believe that driven grouse shooting needs to be banned because it is underpinned by wildlife crime and by degradation of vast landscapes to produce heather for grouse production. We have seen many working examples where rewilding and restoring these landscapes is reversing biodiversity loss, mitigating climate change and boosting rural economies. However, for too long, a softly, softly approach has been taken by some in conservation seeking compromise and middle ground with some landowners, thus perpetuating driven grouse shooting. Some of this appeasement is preventing progress towards the wild restoration we urgently need. With some debates, especially those concerning human or environmental rights, there is no middle ground, although I believe that finding a way forward is to be able to show that everyone can benefit from change. Banning driven grouse shooting and restoring the landscapes will create more rural jobs with long term security for people and the wild.

L: You seem to have a special affinity with birds of prey. Were these birds and their habitats a particular love of yours before you began writing fiction?

G: When I was a child, I desperately hoped a golden eagle would land in my suburban garden. Of course, one never did, but I have always loved the elemental ferocity of birds of prey. Where I live in Somerset, we see many buzzards, but each time still fills me we awe, listening to their wild cry, reminding us that we are all part wild.

L: Did you always write stories, and / or want to be a writer, while you were training and working as a vet?

G: I loved writing stories as a child, but my handwriting and spelling were pretty awful and so I never considered being an author. However, when my children came along, I took them to the library and fell in love with books again. I saw the powerful impact they had on my own children. I loved making up stories to tell them at bedtime or on long car journeys and re-ignited my creative side.

L: Have you any plans to write a non-fiction book about animals and the environment?

G: I would love to and have several ideas to pursue. If someone could find a way of expanding time, that would be great as there are not enough hours in the day!

L: As far as I’m aware, The Closest Thing to Flying is your only novel so far to be set partly in the past. Did you enjoy using a historical setting, and will you be tempted to do so again?

G: I really enjoyed writing a historical setting. However, it meant much research into a time and era I knew little about. The Closest Thing to Flying is in part set in 1891 when women begin to campaign against the use of feathers in fashion. These women were the founders of the RSPB, yet they are only just being recognised now. I found it fascinating to see how ideas and attitudes have changed. I expected these progressive women to be part of the suffragette movement, but in fact some were vehemently anti-suffrage. I think reading and writing historical pieces helps us to revaluate our own belief and opinions. I wonder if they would have changed their opinions on suffrage with the benefit of hindsight. I would love to write a historical piece again and think it might be fun to go way, way back when Britain was joined to Europe by a land bridge.

I have toyed with the idea of writing an imagined future story - a ‘sliding doors’ story to continue Sky Dancer: one future where Minty, the aristocratic daughter of Henry Knight, the moor owner, decides to rewild the estate, and the other future where her brother continues driven grouse shooting. Or maybe there is the third option in the story where the community buys out the land and rewilds it, as has happened with the Tarras Valley Nature Reserve in Scotland.

L: Your books are deservedly popular with readers, and I’m sure they change lives and attitudes. What are some of the best responses you’ve had from young readers?

G: Hearing from readers is always a huge privilege. I’ve been particularly touched by young people who have had cake sales raising money from moon bears to ospreys or writing to MPs about the state of the seas. I have had emails from young people who have gone onto study ecology and marine science from reading by books when they were younger. One letter really moved me to read that because I had written from the perspective of a child with a parent with mental illness, they felt less alone knowing other children lived with that too.

L: And you’re an illustrator too! I loved the cameo portraits of all the dogs in A Street Dog Named Pup. Is this something you’d like to build on, with more illustrated books or even a picture book?

G: I really enjoyed illustrating Pup’s story. Drawing is always essential to my first drafts to find the characters and landscapes. I’m a very visual writer and have to see the story unfold in my head to write it. I’d love to do more illustration, and also find time to experiment with different mediums.

L: What do you find most upsetting in the ways humans treat animals today? And what gives you the most hope for a better future?

G: Turning a blind eye perpetuates many harmful practices. For example, choosing the ‘cute’ face of a dog over the potential life-threatening reality of a severely shortened muzzle, or to the fate of foxhounds that are no longer deemed ‘fit for purpose.’ Many people know that farmed salmon are kept in crowded sea cages, and yet may not pay any mind to the physical suffering and diseases of these fish.

We are more aware and open about addressing mental health issues in humans, but I think we should be more aware of animals as sentient beings. If animals are denied any of the five freedoms, they are prone to suffering mental distress. When someone buys a pup on a whim, and rehomes it a few months later they have failed to see the mental anguish of the pup. Watching dolphins perform for entertainment in small tanks is turning a blind eye to the mental and physical torture of captivity.

Hope for the future comes from knowing that we have many in the younger generation who are more engaged with welfare and environmental issues. More people are changing away from eating animal flesh and animal products to a wholly plant-based diet, hence reducing our reliance on the livestock industry.

L: Are you working on a new book now, and if so can you tell us a little about it?

G: I have just finished a book on beavers for Barrington Stoke. Beavers are landscape engineers and change rivers, creating wetlands, improving water quality, increasing fish-stocks and reducing flooding. The story is about a girl who realises that if a river can change its course, then she can change her life too.

The book I’m writing at the moment is very different. I think last year I felt a sort of ecological grief and after 10 years of writing conservation-based stories, I felt so despondent with the state of the planet and so I’m writing a sort of wild fantasy about rats – and these rats wear clothes! However, there are many parallels to human greed. I’m having a lot of fun writing it.

L: Thank you, Gill - we'll look forward to those!

Find out more about Gill Lewis’s books and work, and also about the background to her stories and the various campaigns she supports, on her website: www.gilllewis.com