I've recently enjoyed Tracy Chevalier's latest novel, AT THE EDGE OF THE ORCHARD, set in nineteenth-century Ohio and California, and now can't think why I hadn't read this one sooner. Its subject - Mary Anning and her fossil discoveries in the early 19th century - is so obviously appealing.

Chevalier's hallmark is to make historical settings and people seem fresh and immediate; she never lets research overload the story or weigh it down with archaic diction. We're soon immersed in the daily and domestic lives of the two first-person narrators. Within pages, we're at Lyme Regis and Charmouth, out on the beach, aware of the incoming tide and the dangers of landslips, eyes peeled for belemnites and the ammonites believed at that time to be coiled snakes.

Both alternating viewpoints are based on historical figures: Elizabeth Philpot, newcomer to Lyme Regis, unmarried in a household of women, finding a keen interest in fossil-hunting; and Mary Anning herself, only ten when the novel begins, uneducated and self-taught, whose regular finds of 'curios' on the beach help her family eke out a living, especially after the death of her father. In fact it's Mary's brother Joe who makes the first astonishing find: a fossilised creature believed at first to be a crocodile but later named ichthyosaurus. Despite the difference in class and an age gap of twenty years, a close association and friendship builds between these two women - Elizabeth at first learning from Mary, later warning her of the risks of a love affair with a man who will never marry her, and more than once taking decisive action to ensure that Mary is given credit for her remarkable discoveries. A serious quarrel between them causes a lasting rift, yet this relationship is the most important in the novel, and through it Chevalier shows us the difficulties for women engaged in science in the early nineteenth-century - how easily their achievements can be purloined by men, and their contributions dismissed as insignificant. The alternating narratives show us the passionate, impulsive yet practical Mary, who believes that she owes her special gift to her survival of a lightning strike as a baby, counterbalanced by the more worldly and rational Elizabeth, who tries to help the Annings through the ups and downs of financial hardship and whose links with London take her into male-dominated institutions such as the Geological Society.

Chevalier's ability to present historical events as if they're unfolding in front of us gives startling impact to the characters' bafflement at the 'monster' fossils Mary finds, seen through the lens of nineteenth-century religious belief. If they are God's creatures, why are none like them alive today? The concept of extinction barely exists - were these animals, then, among those on Noah's Ark, Mary asks at one point? A clergyman, faced with Mary's reasonable question that since God made the land before the animals, how could fossils be embedded in rocks, replies that God must have placed the fossils there to test our faith. The novel places us at the dawn of understanding the true age of the Earth, then believed - according to Bishop Ussher's calculations - to have been a mere 6,000 years old. (Indeed, Bishop Ussher concluded that Heaven and Earth were created on the night preceding the 23rd October 4004 BC: 'I had always wondered at his precision,' Elizabeth reflects.) Mary Anning's discoveries of ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs were significant in shaping evolutionary theory - leading to ideas which revolutionised our view of the human population just as surely as the discovery that the sun, rather than the Earth, is the centre of our universe.

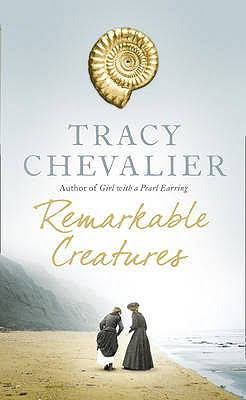

Such big ideas could have overwhelmed the novel in hands less skilled than Chevalier's. We're left with the picture shown on the rather beautiful cover: a headstrong, unconventional girl and her older, more cautious friend, a windswept beach, a search that may prove fruitless or may unlock more of Earth's secrets.

Both Mary and Elizabeth are given recurring motifs. Mary's is the lightning, which she believes courses through her body at moments of revelation, love and - on one occasion - sexual ecstasy. Elizabeth's is her habit of defining people according to which feature they 'lead by'. Mary Anning leads with her eyes; her sister Margaret leads with her hands. Meeting the attractive but possibly manipulative Captain Birch, Elizabeth comments: 'I have never trusted a man who leads with his hair. Only a vain, overconfident man does that.'

I don't know who Tracy Chevalier had in mind when she wrote that phrase. But I know who I'm thinking of now.

Write a comment